Travesties and Encounters

(I doubt if many people -or anyone?- would want to read any part of this website from start to finish. This applies especially to this Travesties and Encounters section, which is meant as something for those who like this sort of thing to dip into.)

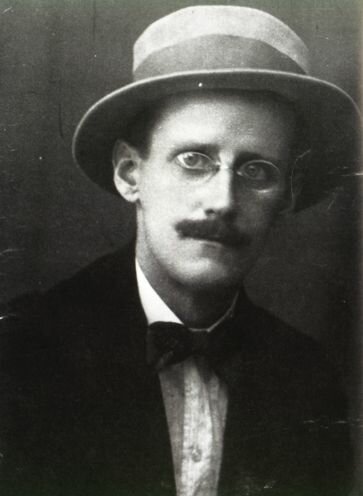

Tom Stoppard's sparkling play Travesties takes off from the fact that Lenin, James Joyce and the Dadaist Tristan Tzara were all living in Zurich during the First World War. In the play they are in the same room in the Zurich library. When the play starts Lenin is getting very excited in Russian about news of a Revolution in Saint Petersburg while Joyce is dictating to an assistant lines like "Morose delectation...Aquinas tunbelly... Frate Porcospino..."

VLADIMIR LENIN JAMES JOYCE

TRISTAN TZARA TOM STOPPARD

Perhaps few real chance meetings are quite as surreal as this, but ever since seeing Travesties I have been interested to hear about improbable or odd encounters. Ones I hear about often involve philosophers. Some are grim. Some are enjoyable. A number of the accounts to follow could be called gossip. People often think of gossip as a minor vice. That may be right when it is malevolent or involves intrusive invasion of the private lives of unwilling people, or even of the possibly willing "celebrities" of whom we hear too much. But, apart from these cases, gossip should be seen as a minor virtue. A person with no interest in gossip has no interest in stories about other people, and so has a drastically reduced capacity to enjoy and celebrate the wonderful peculiarity and diversity of those around us.

WITTGENSTEIN AND HITLER.

Among the darker encounters is that Hitler and Wittgenstein (almost exactly the same age, Hitler being six days older than Wittgenstein) were both schoolboys together in the Realschule at Linz in the year 1903-1904. Academically they were two years apart, as Wittgenstein had been advanced a year and Hitler was year behind. As the school had only about 300 students, it is likely that the two were at least aware of each other.

In the photograph there is no doubt about the identity of the young Hitler, although the correctness of the one marked as Wittgenstein is disputed. (I think the adult Wittgenstein can be glimpsed in the boy's face, but such judgements are obviously fairly subjective.) In Hitler's discussion in Mein Kampf of the origins of his antisemitism, he mentions a Jewish boy at school. It has been claimed (by Kimberley Cornish in The Jew of Linz) that the boy was Wittgenstein. Hitler mentions the Jewish boy in a way that seems to suggest that he was not an important influence on his antisemitism. Having said that he grew up in a home without antisemitism, Hitler goes on: "Likewise at school I found no occasion which could have led me to change this inherited picture. At the Realschule, to be sure, I did meet one Jewish boy who was treated by all of us with caution, but only because various experiences had led us to doubt his discretion and we did not particularly trust him; but neither I nor the others had any thoughts on the matter". It is hard to assess whether or not this boy was Wittgenstein. It is obviously a possibility. It is easy to imagine Wittgenstein both having and communicating a very low impression of Hitler, and that Hitler would not be charmed by this. Hitler's own account denies that the boy influenced his antisemitism, although his claims about his personal history in Mein Kampf cannot be relied on. Whatever the truth about the claimed identity or the influence, the mere fact of the two knowing each other at school would be worthy of Stoppard's wit were the possible implications not so terrible.

THE PHILOSOPHER AS INHUMAN AGONY UNCLE: IMMANUEL KANT RESPONDS TO MARIA VON HERBERT.

Immanuel Kant famously made truth-telling always morally obligatory, regardless of consequences: "To be truthful (honest) in all declarations, therefore, is a sacred and absolutely commanding decree of reason, limited by no expediency".

Maria von Herbert was an enthusiastically Kantian philosopher, as was her husband. Their house was a centre of Enlightenment discussion and of the propagation of rational Kantian morality. In August 1791, Maria von Herbert wrote a letter to Kant about the consequences of her having told someone she loved the truth that she had concealed from him a previous relationship:

Great Kant,

As a believer calls to his God, I call to you for help, for comfort, or for counsel to prepare me for death. Your writings prove that there is a future life. But as for this life, I have found nothing at all that could replace the good I have lost, for I loved someone who, in my eyes, encompassed within himself all that is worthwhile, so that I lived only for him, everything else was in comparison just rubbish, cheap trinkets. Well, I have offended this person, because of a long drawn out lie, which I have now disclosed to him, though there was nothing unfavourable to my character in it, I had no vice in my life that needed hiding. The lie was enough though, and his love vanished. As an honourable man, he doesn't refuse me friendship. But that inner feeling that once, unbidden, led us to each other, is no more - oh my heart splinters into a thousand pieces!If I hadn't read so much of your work I would certainly have put an end to my life. But the conclusion I had to draw from your theory stops me -it is wrong for me to die because my life is tormented. Instead I'm supposed to live because of my being. Now put yourself in my place, and either damn me or conmfort me. I've read the metaphysic of morals, and the categorical imperative, and it doesn't help a bit. My reason abandons me just when I need it. Answer me, I implore you -or you won't be acting in accordance with your own imperative...

Kant replied in Spring 1792:

Your deeply felt letter comes from a heart that must have been created for the sake of virtue and honesty, since it is so receptive to instruction in those qualities. I must do as you ask, namely , put myself in your place, and prescribe for you a pure moral sedative. I do not know whether your relationship is one of marriage or friendship, but it makes no significant difference. For love, be it for one's spouse or for a friend, presupposes the same mutual esteem for the other's character, without which it is no more than perishable sensual delusion.

A love like that wants to communicate itself completely, and it expects of its respondent a similar sharing of heart, unweakened by distrustful reticence. That is what the ideal of friendship demands. But there is something in us which puts limits on such frankness, some obstacle to this mutual outpouring of the heart, which makes one keep some part of one's thoughts locked within oneself, even when one is most intimate...

We can't expect frankness of people, since everyone fears that to reveal himself completely would be to make himself despised by others. But this lack of frankness, this reticence, is still very different from dishonesty. What the honest but reticent man says is true but not the whole truth. What the dishonest man says is something he knows to be false... a lie. It may be harmless but it is not on that account innocent. It is a serious violation of a duty to oneself; it subverts the dignity of humanity in our own person, and attacks the roots of our thinking. As you see, you have sought counsel from a physician who is no flatterer. I speak for your beloved and present him with arguments that justify his having wavered in his affection for you.

Ask yourself whether you reproach yourself for the imprudence of confessing, or for the immorality intrinsic to the lie. If the former, then you regret having doine your duty. And why? Because it has resulted in the loss of your friend's confidence. This regret is not motivated by anything moral, since it is produced by an awareness not of the act itself, but of its consequences. But if your reproach is grounded in a moral judgement of your behaviour, it would be a poor moral physician who would advise you to cast it from your mind.

When your change in attitude has been revealed to your beloved, only time will be needed to quench, little by little, the traces of his justified indignation, and to transform his coldness into a more firmly grounded love. If this doesn't happen, then the earlier warmth of his affection was more physical than moral, and would have disappeared anyway -a misfortune which we often encounter in life, and when we do, must meet with composure. For the value of life, insofar as it consists in the enjoyment we get from people, is vastly overrated.

Here then, my dear friend, you find the customary divisions of a sermon: instruction, penalty and comfort. Devote yourself to the first two; when they have had their effect, comfort will be found by itself.

Maria von Herbert replied in January 1793:

Dear and revered sir,

Your kindness and your exact understanding of the human heart, encourage me to describe to you, unshrinkingly, the further progress of my soul. The lie was no cloaking of a vice, but a sin of keeping something back out of consideration for the friendship (still veiled by love) that existed then. There was a struggle, I was aware of the honesty friendship demands, and at the same time I could foresee the terribly wounding consequences. Finally I had the strength and revealed the truth to my friend, but so late -and when I told him, the stone in my heart was gone, but his love was torn away in exchange. My friend hardened in his coldness, just as you said in your letter. But then afterwards he changed towards me, and offered me again the most intimate friendship. I'm glad enough about it, for his sake -but I'm not really content, because it's just amusement, it doesn't have any point.

My vision is clear now. I feel that a vast emptiness extends inside me, and all around me -so that I almost find my self to be superfluous, unnecessary. Nothing attracts me. I'm tormented by a boredom that makes life intolerable. Don't think me arrogant for saying this, but the demands of morality are too easy for me. I would eagerly do twice as much as they command. They only get their prestige from the attractiveness of sin, and it costs me almost no effort to resist that.

I comfort myself with the thought that, since the practice of morality is so bound up with sensuality, it can only count for this world. I can hope that the afterlife won't be yet another life ruled by these few, easy demands of morality, another empty and vegetating life... I don't study the natural sciences or the arts any more, since I don't feel that I'm genius enough to extend them; and for myself, there's no need to know them. I'm indifferent to everything that doesn't bear on the categorical imperative, and my transcendental consciousness -although I'm all done with those thoughts too.

You can see, perhaps, why I want only one thing, namely to shorten this pointless life, a life which I am convinced will get neither better nor worse. If you consider that I am still young and that each day interests me only to the extent that it brings me closer to death, you can judge what a great benefactor wou would be if you were to examine this question closely. I ask you, because my conception of morality is silent here, whereas it speaks decisively on all other matters. And if you cannot give me the answer I seek, I beg you to give me something that will get this intolerable emptiness out of my soul. Then I might become a useful part of nature, and, if my health permits, would make a trip to Konigsberg in a few years. I want to ask permission, in advance, to visit you. You must tell me your story then, because I would like to know what kind of life your philosophy has led you to -whether it never seemed to you to be worth the bother to marry, or to give your whole heart to anyone, or to reproduce your likeness. I have an engraved portrait of you by Bause, from Leipzig. I see a profound calm there, and moral depth -but not the astuteness of which the Critique of Pure Reason is proof. And I'm dissatisfied not to be able to look you right in the face.

Please fulfill my wish, if it's not too inconvenient. And I need to remind you: if you do me this great favour and take the trouble to answer, please focus on specific details, not on the general points, which I understand, and already understood when I happily studied your works at the side of my friend. You would like him, I'm sure. He is honest, goodhearted, and intelligent -and besides that, fortunate enough to fit this world.

I am with deepest respect and truth, Maria Herbert.

Kant asked a mutual friend, Erhard, about Maria Herbert, and was told that she had "capsized on the reef of romantic love". In February 1793 he wrote to Elizabeth Motherby, the daughter of one of his friends, enclosing the two letters from Maria Herbert and the one from Erhard. Kant's letter to Elizabeth Motherby read:

I have numbered the letters which I have the honour of passing on to you, my dear mademoiselle, according to the dates I received them. The ecstatical little lady didn't think to date them. The third letter, from another source, provides an explanation of the lady's curious mental derangement. A number of expressions refer to writings of mine that she read, and are difficult to understand without an interpreter.

You have been so fortunate in your upbringing, that I do not need to commend these letters to you as an example of warning, to guard you against the wanderings of a sublimated fantasy. But they may serve nonetheless to make your perception of that good fortune the more lively.

I am, with the greatest respect, my honoured lady's most obedient servant, I Kant.

Kant never replied to Maria Herbert's second letter. In 1803 she committed suicide.

These letters are extracted from a sensitive and perceptive discussion of what they tell us about Kant's moral philosophy by Rae Langton: Duty and Desolation, Philosophy, 1992. There is a shortened version in Peter Singer (ed.): Ethics, Oxford University Press, 1994.

HEGEL LUNCHES WITH GOETHE AND HIS FAMILY.

It was lunch at the Goethe's, and Goethe himself was quiet,

... no doubt not to disturb the free speech of his very voluble and logically penetrating guest, who elaborated upon himself in oddly complicated grammatical forms. An entirely novel teminology, a mode of expression mentally overleaping itself, the peculiarly employed philosophical formulas of the ever more animated man in the course of his demonstrations -all this finally reduced Goethe to complete silence without the guest even noticing...

One of the others at the meal said afterwards, "I cannot tell whether he is brilliant or mad. He seems to me to be an unclear thinker."

Account by Ottilie von Goethe, quoted in Geoffrey Hawthorne: Hegel's Odyssey, London Review of Books, October, 1985.

SCHELLING'S LECTURES.

iN 1841, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling was lecturing in Lecture Hall 6 in the University of Berlin. In the audience was Friedrich Engels: "alongside him perched Jacob Burkhardt, the nascent art historian and Renaissance scholar; Michael Bakunin, the future anarchist (who dismissed the lectures as "interesting but rather insignificant"); and the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, who thought Schelling talked "quite insufferable nonsense"."

Tristram Hunt: The Frock-Coated Communist, the Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels, Allen Lane, 2009.

Those of us who give lectures or classes in philosophy may be a bit saddened, though not entirely surprised, if some of the audience feedback describes the content as "rather insignificant" or "insufferable nonsense". (In the section of this website called Philosophy, Beliefs and Conflicts, my lecture on "The Philosophy and Psychology of a New World Order" has been taken from Youtube. With it have come a couple of splendid examples of comments of this sort.) Even a huge quantity of negative or inane feedback would be a price worth paying to have a class including the people in Schelling's.

LONDON PUBS AND THE EARLY DAYS OF COMMUNISM.

Lenin worked in Clerkenwell as editor of the revolutionary paper Iskra (The Spark) from 1902 until 1903. The office was at 37a Clerkenwell Green. Stalin, having met Lenin at a 1905 conference in Finland, visited him that year in London, and local legend has it that they used to talk together in the Crown and Anchor pub (now the Crown Tavern) on Clerkenwell Green.

It is unlikely that Lenin and Stalin having a drink together would make for a particularly convivial occasion. I would have prefered to eavesdrop on the pub conversations of Marx and Engels. After moving to Primrose Hill in 1870, Engels used to walk over from Regent's Park Road to Marx's house in Maitland Park Villas for their daily talk together. Often their talk would take place on a long walk over Hampstead Heath, and would continue the conversation as they ended by having a drink at Jack Straw's Castle.

We do not know for sure what Lenin and Stalin may have discussed at the Crown and Anchor, or what Marx and Engels talked about at Jack Straw's Castle. We do know what was discussed at the second congress of the Communist League at the end of 1847 in the room above the Red Lion pub in Great Windmill Street, Soho. For ten days the League met in this room and argued about their basic principles, ending in victory for the views of Marx and Engels that were to be the basis of the Communist Manifesto.

The depictions of Marx in the gargantuan statues erected in Moscow, East Berlin and other parts of the former communist world might suggest an intellectual giant, dedicated only to developing and acting on theories of the dialectic and the class struggle. For such an unremittingly granite thinker and fighter, pubs would have served only as convenient places for political discussion and debate.

MARX NEAR THE BOLSHOI THEATRE.

MARX AND ENGELS NEAR ALEXANDERPLATZ.

But parts of Marx's actual life make a nice contrast to the granite version. One night Marx walked up the Tottenham Court Road with Wilhelm Liebknecht and Edgar Bauer. They planned to have a glass of beer in each of the eighteen pubs between Oxford Street and what is now the Euston Road. In the last pub they got into a drunken row with some Englishmen and had to escape. Then Bauer stumbled over a heap of paving stones and threw one at the gas lantern, smashing the glass. Francis Wheen, in his very lively biography of Marx, quotes Liebknecht's account: "Marx and I did not stay behind, and we broke four or five street lamps -it was, perhaps, two o'clock in the morning and the streets were deserted... But the noise nevertheless attracted the attention of a policeman who with quick resolution gave the signal to his colleagues... The position became critical... We raced ahead, three or four policemen some distance behind us. Marx showed an agility that I should not have attributed to him. And after the wild chase had lasted some minutes, we succeeded in turning into a side street, and there through an alley -a back yard between two streets- whence we came behind the policemen who lost the trail. Now we were safe. They did not have our description and we arrived at our homes without further adventures."

STALIN'S PHILOSOPHY TUTOR.

Stalin asked his assistant to assemble a library of books for him and he put philosophy first on the list of subjects to be included. He then appointed the philosopher Jan Sten to be his tutor. Sten must have thought that he had a chance of influence not given to any philosopher since Aristotle taught Alexander the Great. He drew up a programme to teach Stalin about Kant, Hegel, Fichte, Schelling, Feuerbach, Plekhanov, Kautsky and F.H.Bradley. In the tutorials, Stalin sometimes asked questions like "What's all this got to do with the class struggle?" or "Who reads all this rubbish in practice?"

Despite his impatience, Stalin persevered with the subject enough to think of himself as a philosopher. In 1930 he gave a philosophical lecture to an institute of professors, which is summarized in the minutes:

"We have to turn upside down and dig over the whole pile of manure that has accumulated in philosophy and the natural sciences. Everything written by the Deborin group has to be smashed. Sten and Karev can be chucked out. Sten boasts a lot, but he's juist a pupil of Karev's. Sten is a desperate sluggard. All he can do is talk. Karev's got a swelled head and struts about like an inflated bladder. In my view, Deborin is a hopeless case, but he should remain as editor of the journal so we'll have someone to beat. The editorial board will have two fronts, but we'll have the majority."

After this philosophy lecture there were questions. Unsurprisingly, they were undemanding. One was, "What should the Institute concentrate on in the area of philosophy?" Stalin replied:

"To beat, that is the main issue. To beat on all sides and where there hasn't been any beating before. The Deborinites regard Hegel as an icon. Plekhanov has to be unmasked. He always looked down on Lenin. Even Engels was not right about everything. There is a place in his commentary on the Erfurt Programme about growing into socialism. Bukharin tried to use it. It wouldn't be a bad thing if we could implicate Engels somewhere in Bukharin's writings."

It would be a nightmare for any philosophy tutor to give tutorials to Stalin. And a tutor might be depressed at being described as a desperate sluggard by the most famous person he had taught. But things got worse. Jan Sten was later described as a lickspittle of Trotsky and executed.

From Humanity, a Moral History of the Twentieth Century.

WAR SERVICE: PEREGRINE WORSTHORNE TWICE HOPES TO IMPRESS THE ADMINISTRATION OFFICER OF PHANTOM.

Doing his Second World War service in the army, Peregrine Worsthorne -later a distinguished conservative journalist- was assigned to the intelligence organization "Phantom":

Back at B Squadron I became friendly with the administration officer, Captain Michael Oakeshott. He seemed to be amused by my company which was very flattering since he was much older and of senior rank. There was also something intriguely different about him... Then there was the matter of my overcoat. Before coming out to Holland I had got my tailor to run me up one in fur, the sole purpose of which, I maintained, was to keep the cold out. Not all my fellow officers agreed... Just when the critics were on the edge of convincing Peter Patrick to ban the garment, Michael Oakeshott successfully intervened on my behalf with a decisive quotation from the Duke of Wellington to the effect that "dandies make the best soldiers". What I had no idea of at the time was that Michael Oakeshott, in civilian life, was already a famous Cambridge philosopher; nor, I think, did anybody else... after dinner in the evening we sometimes had informal debates at which I would try desperately to shine in an effort to show that being bad at map reading did not necessarily make one a complete fool. Although Michael used to giggle joyously he never took part.

THE ADMINISTRATION OFFICER, PHANTOM.

After the war Peregrine Worsthorne went back as an undergraduate to Cambridge:

My only regret was not being able to finish the course of lectures in political philosophy by one M.J. Oakeshott, who turned out to be my old Phantom comrade-in-arms... he had never given me any idea of his true identity during the war. So his appearance on the podium at my first lecture in cap and gown took me completely by surprise. Typically he only giggled when he saw me staring up at him from the front row. Just as he had made no fuss of his academic eminence in the army, so now he made no fuss of it back at Cambridge. After the lecture we went off together to have coffee at the Copper Kettle in King's Parade as if nothing had changed. But it had. Now I was a bit overawed by him, anxious to impress and since what he liked in the young was cheek and arrogance, my new respectfulness was the last thing to give pleasure. A few years later, after my marriage, he became our lodger in London. But by then it was in the company of my wife that he found the zest and exuberance which in the army he had found in mine.

Peregrine Worsthorne: Tricks of Memory.

WAR SERVICE: CAPTAIN EVELYN WAUGH DESCRIBES HIS COLONEL AT KELBURN CASTLE, GIVING SOME HELP TO LORD GLASGOW.

EVELYN WAUGH.

KELBURN CASTLE.

So No. 3 Cmdo were very anxious to be chums with Lord Glasgow so they offered to blow up an old tree stump for him and he was very grateful and he said dont spoil the plantation of young trees near it because that is the apple of my eye and they said no of course not we can blow a tree down so that it falls on a sixpence and Lord Glasgow said goodness you are clever and he asked them all to luncheon for the great explosion. So Col. Durnford-Slater D.S.O. said to his subaltern, have you put enough explosive in the tree. Yes, sir, 75 lbs. Is that enough. Yes sir I worked it out by mathematics it is exactly right. Well better put a bit more. Very good sir.

And when Col. D. Slater D.S.O. had had his port he sent for the subaltern and said subaltern better put a bit more explosive in that tree. I don't want to disappoint Lord Glasgow. Very good sir.

Then they all went out to see the explosion and Col. D.S. D.S.O. said you will see that tree fall flat at just that angle where it will hurt no young trees and Lord Glasgow said goodness you are clever.

So soon they lit the fuse and waited for the explosion and presently the tree, instead of falling quietly sideways, rose 50 feet into the air taking with it 1/2 acre of soil and the whole of the young plantation.

And the subaltern said Sir I made a mistake, it should have been 7&1/2 pounds not 75.

Lord Glasgow was so upset he walked in dead silence back to his castle and when they came to the turn of the drive in sight of his castle what should they find but that every pane of glass in the building was broken.

So Lord Glasgow gave a little cry & ran to hide his emotion in the lavatory and there when he pulled the plug the entire ceiling, loosened by the explosion, fell on his head.

This is quite true.

Letter to Laura Waugh, 31 May 1942, in Mark Amory (ed.): The Letters of Evelyn Waugh.

AIR MARSHALL SIR ARTHUR HARRIS AND THE REV. JOHN COLLINS.

In the Second World War, the saturation bombing of German cities was masterminded by Air Marshall Sir Arthur Harris. (In the chapter about this policy in Humanity, a Moral History of the Twentieth Century I agreed with those who see this policy as a war crime.)

The moral case for area bombing was contested within Bomber Command itself. The chaplain at Bomber Command Headquarters at High Wycombe was John Collins. (In the 1960s, and by then Canon Collins, he was a well-known leader of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. There is something surreal about John Collins and Sir Arthur Harris having to work together.)

John Collins invited the Minister of Aircraft Production, Sir Stafford Cripps, to give a talk on the subject "Is God My co-pilot?". Cripps argued that officers should only send men on bombing raids which they thought were morally as well as militarily justified.

Sir Arthur Harris replied by arranging a lecture on "The Ethics of Bombing". This was given by T.D. ("Harry") Weldon. a Fellow in Philosophy at Magdalen College, Oxford. He later wrote a book on Kant and an austere linguistic work on political philosophy. The Vocabulary of Politics. He was Personal Staff Officer to Sir Arthur Harris in Bomber Command and drafted the communications Harris sent to the Cabinet and the Air Ministry. Predictably, his talk was rather different from that given by Cripps. When Weldon had finished, Collins asked whether Weldon had not taken his subject to be "The Bombing of Ethics"?

(Sir Arthur Harris comes out of this story with some credit. It is hard to imagine the German equivalents of John Collins and Sir Stafford Cripps using Luftwaffe headquarters for an ethical lecture critical of the German bombing policy. And, if they had, Hermann Goering's response might not have taken the form of a rival lecture by a philosopher.)

From Humanity, a Moral History of the Twentieth Century.

STUART HAMPSHIRE INTERROGATES ERNST KALTENBRUNNER.

Stuart Hampshire was one of the most civilized and fastidious of philosophers. At the Nuremberg trials, Ernst Kaltenbrunner gave an impression of cold brutality extreme even by Nazi standards. (During the trial, where the horrors he was so deeply invoved in were spelt out, he wrote, "No one will find us weak! What a splendid feeling to have lived a life that demanded and found danger and readiness for action".) It would have been fascinating to eavesdrop on Hampshire's conversations with Kaltenbrunner. His own brief account is very reticent. It is reproduced here partly because he indicates the interweaving -too rarely made explicit- of philosophy and personal experience.

It therefore began to seem necessary that philosophy should finally abandon its shortcuts and its grandiose claims and should proceed in the tentative problem-solving style of the natural sciences. With this idea the study of the peculiarities of natural languages came to be considered a central part of philosophy. Then came the war, long anticipated. As an intelligence officer in the war for four years I studied the espionage and counter-espionage operations of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, Himmler's Central Command, which controlled the whole of the SS, including the Gestapo, excluding only the Waffen SS. This experience altogether changed my attitude both to politics and to philosophy, as the full scale of the SS's operations in occupied Europe and in Russia became known, and as the programme announced in Mein Kampf could be studied in action. I interrogated some leading Nazis in captivity at the end of the war, including Heydrich's successor as head of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, Kaltenbrunner, with whom I talked at length when he was a prisoner with U.S. Army headquarters, and whom I brought to London for further interrogation. I learnt how easy it had been to organise the vast enterprises of torture and of murder, and to enrol willing workers in this field, once all moral barriers had been removed by the authorities. Unmitigated evil and nastiness are as natural, it seemed, in educated human beings as generosity and sympathy: no more, and no less, natural, a fact that was obvious to Shakespeare but not previously evident to me.

Stuart Hampshire: Innocence and Experience.

T.S. ELIOT READS THE WASTE LAND TO THE ROYAL FAMILY.

A.N. Wilson wrote about a lunch with the Queen Mother. She talked about an occasion when, as part of the education of her daughters Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret, T.S. Eliot had been invited to read some of his poetry to the Royal Family. She remembered "this rather lugubrious man in a suit, and he read a poem... I think it was called "The Desert". At first the girls got the giggles and then I did and then even the King... Such a gloomy man, looked as though he worked in a bank."

T.S. ELIOT ATTENDS A TALK BY BERTRAND RUSSELL.

When Mr. Apollinax visited the United States

His laughter tinkled among the teacups.

I thought of Fragilion, that shy figure among the birch trees,

And of Priapus in the shrubbery

Gaping at the lady in the swing.

In the palace of Mrs. Phlaccus, at Professor Channing-Cheetahs

He laughed like an irresponsible foetus.

His laughter was submarine and profound

Like the old man of the sea's

Hidden under coral islands

Where worried bodies of drowned men drift down in the green silence,

Dropping from fingers of surf.

I looked for the head of Mr. Apollinax rolling under a chair

Or grinning over a screen

With seaweed in its hair.

I heard the beat of centaur's hoofs over the hard turf

As his dry and passionate talk devoured the afternoon.

"He is a charming man"- "But after all what did he mean?" -

"His pointed ears... He must be unbalanced."-

"There was something he said that I might have challenged."

Of dowager Mrs. Phlaccus, and Professor and Mrs. Cheetah

I remember a slice of lemon, and a bitten macaroon.

PHILOSOPHER KINGS? THE TWO APPROACHES MIGHT BE HARD TO COMBINE: BERTRAND RUSSELL AND KING GEORGE VI.

Some years before I gave the Reith Lectures, my old professor and friend and collaborator in Principia Mathematica, A.N. Whitehead, had been given the OM. Now, by the early part of 1950, I had become so respectable in the eyes of the Establishment that it was felt that I, too, should be given the OM. This made me very happy for, though I daresay it would surprise many Englishmen and most of the English Establishment to hear it, I am passionately English, and I treasure an honour bestowed on me by the Head of my country. I had to go to Buckingham Palace for the official bestowal of it. The King was affable, but somewhat embarrassed at having to behave graciously to so queer a fellow, a convict to boot. He remarked, "You have sometimes behaved in a way which would not do if generally adopted". I have been glad ever since that I did not make the reply that sprang to my mind: "Like your brother." But he was thinking of things like my having been a conscientious objector, and I did not feel that I could let this remark pass in silence, so I said, "How a man should behave depends upon his profession. A postman, for instance, should knock at all the doors in a street at which he has letters to deliver, but if anybody else knocked on all the doors, he would be considered a public nuisance." The King, to avoid answering, abruptly changed the subject by asking me whether I knew who was the only man who had both the KG and the OM. I did not know, and he graciously informed me that it was Lord Portal.

Bertrand Russell: Autobiography, Volume 2.

NIELS BOHR AND CHURCHILL: "WE DID NOT SPEAK THE SAME LANGUAGE".

Bohr escaped from occupied Denmark. Because of the threat of a Nazi bomb, he was willing to work on the Manhattan Project. He started to think about the deeper problems of atomic weapons and realized that, since the United States had made the bomb, the Soviet Union would soon follow. The choice was simple: international control or a nuclear arms race. He saw international control as the only safe option...

Bohr returned to England, and persuaded the President of the Royal Society, Sir Henry Dale, of the importance of the issue. Dale was among those who persuaded Churchill to see Bohr. Thinking of voluntary abstention from using the bomb, in the interests of future international control, Dale wrote to Churchill: "It is my serious belief that it may be in your power even in the next six months to take decisions which will determine the future course of human history. It is in that belief that I dare to ask you, even now, to give Professor Bohr the opportunity of brief access to you."

Privately, Dale expressed the fear that Bohr's "mild, philosophical vagueness of expression and his inarticulate whisper" might mean that he would not get through to "a desperately preoccupied Prime Minister".

The meeting was not a success. Lord Cherwell was present and much of the time was taken up with argument between him and Churchill on points irrelevant to Bohr's purpose. According to Bohr's own "very vivid memories" of the interview, recounted to Margaret Gowing, the main point was never reached. "Professor Bohr was unable to bring the Prime Minister's mind to bear on the implications of the bomb or to tell him of his belief that the President himself was giving the subject such serious thought." Churchill disliked the meeting. Bohr asked if he could send a memorandum on the subject to Churchill:

The Prime Minister replied that he would always be honoured to receive a letter from Professor Bohr but hoped that it would not be about politics. Bohr came away greatly disappointed at the way the world was apparently governed, with small points exercising a quite irrational influence. "We did not speak the same language," said Bohr afterwards.

From Humanity, a Moral History of the Twentieth Century.

PHILOSOPHERS ARE NOT ALWAYS SERENE. 1: WITTGENSTEIN REPLIES TO OSCAR WOOD'S UNDERGRADUATE PAPER ON DESCARTES, FOLLOWED BY AN EXCHANGE WITH H.A. PRICHARD.

LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN.

H.A. PRICHARD.

Wittgenstein started his reply (uttered in tones of disgust and disbelief) with the words "Mr. Wood seems to me to have made two points". He then abandoned Mr. Wood and Descartes altogether and started to talk in his own style about what "the cogito" could possibly be thought to mean. At one point he said, "If a man says to me, looking at the sky, "I think it will rain therefore I exist" I do not understand him" upon which a very old philosopher, H.A Prichard... interrupted with "That's all very fine; but what I want to know is, is the cogito a valid argument or not?". Prichard was very deaf, his voice was ancient and querulous, and he had a terrible cough, but he interrupted three or four times. Wittgenstein never once mentioned Descartes, and at one point was provoked into saying that Descartes was of no importance. Prichard's last contribution was, "What Descartes was interested in was far more important than any problem you have addressed this evening", and with that he tottered out. There was considerable embarrassment, as I recorded in my diary, at Prichard's rudeness. It proved to be his last outing. He was dead within a week.

Mary Warnock: A Memoir: People and Places.

PHILOSOPHERS ARE NOT ALWAYS SERENE. 2: ELIZABETH ANSCOMBE ATTENDS THE CLASSES OF J.L. AUSTIN.

Elizabeth attended these classes, I suppose, in part, to observe Austin in action... but also as the champion, or even the spy, of Wittgenstein. In any case she was a troublesome presence and frequently intervened to pour scorn on what was being said. On one particular evening, when she had behaved with notable rudeness, I tried to evade her afterwards by scuttling very fast out of the Magdalen back gates, but she caught up with me as I was struggling with my bicycle lock in Longwall, and hissed "To think that Wittgenstein fathered that bastard".

Mary Warnock: A Memoir: People and Places.

ACROSS 103 YEARS: SLAVOJ ZIZEK AND G.E. MOORE.

When we perceive something as an act of violence, we measure it by a presupposed standard of what the "normal" non-violent situation is -and the highest form of violence is the imposition of this standard with reference to which some events appear as "violent". This is why language itself, the very medium of non-violence, of mutual recognition, involves unconditional violence. In other words, it is language itself which pushes our desire beyond proper limits, transforming it into a "desire that contains the infinite", elevating it into an absolute striving that cannot ever be satisfied.

Slavoj Zizek: Violence, Six Sideways Reflections, 2008.

My brother has just published a book on Durer. There is a great deal of philosophy in it, which begins with this sentence: "I conceive the human reason to be the antagonist of all forces other than itself". I do wish people wouldn't write such silly things -things, which, one would have thought, it is so perfectly easy to see to be just false. I suppose my brother's philosophy may have some merits; but it seems to me just like all wretched philosophy -vague, and obviously inconsequent, and full of falsehoods. I think its object is to be like a sermon -to make you appreciate good things; and I sometimes wonder whether it is possible to do this without saying what is false. But it does annoy me terribly that people should admire such things -as they do.

G.E. Moore: Letter to Leonard Woolf, 1905.

VIRGINIA WOOLF VISITS H.A.L. FISHER WHEN HE WAS WARDEN OF NEW COLLEGE.

Staying with the Fishers. A queer thing, people who accept conventions. Gives them a certain force. H[erbert] has the organisation behind him. But robs them of character, of vagaries, of depth, warmth, the unexpected. They spin along the grooves. H to some extent anxious to impress his privileged impartial position. Many stories of "when I was in the Cabinet". Yet why not? The odd thing is that when with them one accepts their standards. And whats wrong? So nice, just, equable, humane. But how chill! And over his shoulder I see the rulers; small; but not evil; striving, -a complex impression. Wardens have lived there since 1370 -or so. How can he differ?... Yes, Herbert accepts the current values, only rather intellectualises & refines... Tells stories of Balfour & in the manner of the great man -discreet, nipped, bloodless, like a butler used to the best families. Toils at history of Europe. Is an example. Do their duty by the college. Represent culture, politics, worldly wisdom gilt with letters. Nothing to whizz one off one's perch at New College: all in good taste, & very kind. But Lord to live like that!

Virginia Woolf: Diary, 4 December, 1933.

PENELOPE FITZGERALD VISITS STEVIE SMITH.

PENELOPE FITZGERALD.

STEVIE SMITH.

In 1969, Penelope Fitzgerald and her daughter Tina went to lunch with Stevie Smith at her house in Palmer's Green. It is hard to know whether it would be more intimidating to be visited (and perhaps described) by Virginia Woolf or by Penelope Fitzgerald:

Combination of shrewd business woman, genuine artist, lonely middle-aged woman anxious to please, and mad-woman. House where she had lived for 61 years with her aunt... not changed in all that time... Upstairs, aunt's bedroom just as she left it when she died, freezing cold... Downstairs in the basement, stone sink, ancient stove with stovepipe, might have come out of La Boheme, faint mould... a cupboard with bits of tarnished silver... fluted gilt teacups, Japanese teapots, no lids, nut-crackers, dim cruets; Stevie struggling mysteriously with the lunch, a large tough chicken... There were squares of carpet on the floor -we thought they were samples and she was choosing a new one -they were samples, but she had got them free and was sticking them together to make a carpet. Evidently it was too late for her now to learn to cook; she looked dwarfed by the huge thick plates and forks; she had bought some large white tombstone-like meringues from the local shop; felt distressed by her going to this trouble.

Penelope Fitzgerald's typed account of the visit, found inside her copy of Stevie Smith's The Frog Prince, quoted by Hermione Lee, the Guardian, April 3, 2010.

THE TWELVE YEAR OLD JOHN BETJEMAN SHOWS HIS POEMS TO A TEACHER.

I couldn't see why Shakespeare was admired;

I thought myself as good as Campbell now

And very nearly up to Longfellow;

And so I bound my verse into a book,

The Best of Betjeman, and handed it

To one who, I was told, liked poetry -

The American master, Mr. Eliot.

That dear good man, with Prufrock in his head

And Sweeney waiting to be agonized,

I wonder what he thought? He never says

When now we meet, across the port and cheese.

He looks the same as then, long, lean and pale,

Still with the slow deliberating speech

And enigmatic answers. At the time

A boy called Jolly said "He thinks they're bad"-

But he himself is still too kind to say.

John Betjeman: Summoned by Bells.

MARCELLE QUINTON HELPS ISAIAH BERLIN PACK HIS TRUNK AND NOTICES HIS KUMQUATS.

In 1952 Isaiah Berlin was delivering the Flexner Lectures at Bryn Mawr. He brought letters from Tony and I helped him pack his trunk. On the mantelshelf in his room at the Deanery, which I needed special permission to visit, he had about half a dozen jars full of kumquats in syrup. I eventually found out that he took them out only as far as his fingers could descend into the jar, his great mind not thinking either of decanting or even using a spoon.

Marcelle Quinton, in Marcelle and Anthony Quinton: Before We Met.

ALAN BENNETT FINDS CONVERSATION EASIER WITH A WORLDLY PHILOSOPHER THAN WITH AN UNWORLDLY ONE.

In the evening to the Savile with Mary-Kay for the Hawthornden Prizegiving. I sit between Anthony Quinton and Iris Murdoch and am grateful for the worldliness of one and the unworldliness of the other, Quinton chatting easily and with seeming gusto and also being very funny despite having flown back from Boston that day, while Dame Iris keeps up a constant flow of questions ("Where do you live?" "Do you drive a car?" What colour is it?" "Where have you parked?"). a nice purling stream as she tucks into the Savile's duck, followed by apple sorbet.

Alan Bennett: Diaries 1980-1990, in Writing Home

ANTHONY QUINTON.

ALAN BENNETT.

IRIS MURDOCH.

IRIS MURDOCH DOES A KINDNESS TO ELIZABETH ANSCOMBE AND GEORG KREISEL.

ELIZABETH ANSCOMBE.

GEORG KREISEL.

I could record one other cooking experience in Iris's life, and one I still find quite upsetting to remember. It must have taken place about the time I first met her, or perhaps before I met her. Two friends of hers, the strong-minded female philosopher who practised "telegamy", and a mathematical logician of international standing who was a bachelor, had asked to borrow her room for a day while she was absent. The room she then lived in had a gas-ring and wash-basin but not much else, and they required it not for secret sexual congrress but because the mathematician wanted to indulge himself in a culinary experiment. Why they should have required Iris's room for this purpose I still cannot fathom, except that the room was handy and that they knew they could presume on her discretion and her unbounded good nature. (They were right of course, but I still grind my teeth when I think of it, even though they are not my own teeth any more but false ones, a denture.) The experiment was in the manufacture of herring soup, which the mathematician, Viennese but possibly with Baltic origins, swore he was on the verge of perfecting. The philosopher affected not to believe him, and swore in her turn -she was a lady with a strong streak of Puckish humour- that she could never be induced under any circumstances to partake of such a dish, however exquisitely prepared. The very idea of it was repellent to her. So they made what amounted to a bet.

The mathematician won the bet. The soup was a triumph: the philosopher capitulated and said that it was so. Indeed she consumed it with relish. When Iris returned a few days later it was to find her room in the most gruesome possible disorder, smelling strongly of fish, and her landlady furious. Other tenants had complained of the noise and the smell. Miss Murdoch's reputation, once immaculate, was now in ruins. In the eyes of the landlady she was, and remained, a fallen woman: one who allowed the most unspeakable orgies to take place in her room, and no doubt participated in them herself. Iris left the house not long after, although its position and amenities had suited her very well. But that was not what upset me when Iris told me the tale, which she did in a tolerant amused way, without a trace of resentment.

Indeed she remained, and still does, on the best possible terms with both parties, even though neither attempted an apology for what had taken place, or even seemed to think one might be appropriate. It annoys me intensely that she should still revere them, none the less. But what upset me even more, and for some reason can still go through me like a spear, was that Iris found one of her most treasured possessions lying on the floor of the room, hideously violated. It was a blue silk chiffon scarf which her mother had given her as a special birthday present. Its state when discovered was so repulsive that Iris had no choice but to take it straight out to the dustbin, holding her nose while she did so. The logician had required the finest possible sieve to strain the end product of his masterpiece, and the philosopher, casually opening a drawer, had handed him the scarf.

I can still see and imagine the pair, wringing out the last drop. I have only met either of them a few times, but when I do I find it difficult to be more than barely civil.

John Bayley, Iris.

ELIZABETH ANSCOMBE WAS ALSO A HERO: PRESIDENT TRUMAN'S OXFORD DEGREE.

Suppose using the bomb had been the only way of shortening the war. Would it then have been justified? One contribution to this debate was made in 1956, when it was proposed that Oxford University should award an honorary degree to President Truman. Proposals for honorary degrees were always accepted and few university members bothered to vote on them. But on the day Truman was proposed, Congregation was full because there was a controversial proposal to include less Greek New Testament in the Theology degree.

One witness described the occasion: "The House was preparing to snooze through the routine business before coming to what was the real reason for their presence, but suddenly and startlingly, Miss Anscombe rose and (after duly seeking the VC's [Vice Chancellor's] permission to speak English) delivered an impassioned speech against the award of an Oxford degree to the "man who pressed the button" of the Bomb. The VC called for a vote: she was in a minority of one."

The speech elicited only "the complete silence and impassivity of those present... not the slightest sign of approval or disapproval, not a murmur, not a rustle, not a change of countenance, but only utter impeturbability." Memories of the occasion vary. In a different account, four people voted against the degree, including another philosopher, Philippa Foot.

The content of Elizabeth Anscombe's speech is reproduced in a paper she published at the time on "Mr. Truman's Degree". She correctly saw how area bombing had paved the way for the atomic bomb. She accepted that, in the circumstances, dropping the bomb probably saved many lives, but pointed out that the circumstances included the Allies' demand for unconditional surrender and their disregard for Japan's known desire for a negotiated peace.

Elizabeth Anscombe's central moral claim was that to kill innocent people as a means to an end is always murder. The state has a right to order killing in a war fought either to protect its own people or to protect others who are treated unjustly. There is no right intentionally to kill innocent people, those who are neither waging the war nor supplying its means. Attacking military targets as carefully as possible may involve unintended but foreseen civilian deaths, and this is not murder. But it is not acceptable to attack where the military objective can only be hit by taking as your target something which includes large numbers of innocent people: "Then you cannot very well say they died by accident. Here your action is murder."

Elizabeth Anscombe finished on a rhetorical flourish. She said that she would fear to go to the degree ceremony "in case God's patience suddenly ends". Afterwards Harry Weldon, Air Marshall Harris's former colleague, offered to arrange comprehensive air cover.

It is hard to warm to the response of those who heard Miss Anscombe and then voted in a way that left her in such a small minority. Just possibly, each person who voted against her may have had good reasons. But their silence and utter impeturbability now seem extraordinary. Was there too little time for discussion, because of the pressing issue of Greek New Testament in the Theology degree? Did no-one think that this courageous and powerful speech deserved the compliment of rational opposition? Apart from Philippa Foot, where were the philosophers?

From Humanity, a Moral History of the Twentieth Century.

AYER ALSO WAS A HERO: FREDDIE AYER, NAOMI CAMPBELL AND MIKE TYSON.

A woman came into a party in a New York appartment saying that her friend was being assaulted in a bedroom. Freddie Ayer investigated and, finding Mike Tyson forcing himself on the young Naomi Campbell, told him to stop. In A.J. Ayer, Ben Rogers reports the resulting conversation:

"Do you know who the fuck I am? I'm the heavyweight champion of the world." Ayer stood his ground. "And I am the former Wykeham Professor of Logic. We are both pre-eminent in our field. I suggest that we talk about this like rational men." Ayer and Tyson began to talk. Naomi Campbell slipped out.

MIKE TYSON.

FREDDIE AYER.

FREDDIE AYER AND RICHARD WOLLHEIM VISIT THE SAME LADY. RICHARD WOLLHEIM DESCRIBES THE BALLET OF HIS REMOVAL.

RICHARD WOLLHEIM.

The voice on the telephone begged me to come round. There was a man there. He might, he might, be a bore. I left the lodge, walked out into the garden, stepped over the wall of the churchyard, and in two minutes was knocking at the door. The man there, who was perhaps not altogether pleased to see me, was, I quickly realized, no ordinary person. He was in his late thirties, not tall, with dark wavy hair, parted near the centre of his head, which from time to time he combed back -combed back rather than brushed back- with his fingers... But it was the movement, the constant movement, of head, hands, fingers, hair, -the playing with the watch-chain, one bit rubbed against another, the feet going backwards, forwards, shuffling, tapping, turning on his heel and sotto voce a stream of "Yes, yes, yes" -it was this incessant movement, this constant stream of excitement, that so impressed me. It convinced me that I was in the presence of someone quite remarkable, and it was also it that led to a curious misunderstanding. The ballet was in Oxford that week, and I was almost convinced that my hostess had introduced the man as "Freddie Ashton", the dancer, the choreographer, who had made something out of English ballet. Certainly I had, for a start, never seen anyone else in 4 Holywell quite so unoppressed by the heat. The stamina of all that training, I thought. I have no idea what the three of us found to say, but, about half an hour later, as the man was making to go, I followed him into the night air and down two steep steps on to the pavement, when suddenly with a daring balletic movement he leapt round me, jumped back into the house, and slammed the door behind him. I was confirmed in my misunderstanding.

Richard Wollheim: Ayer: the Man, the Philosopher, the Teacher, in A. Phillips Griffiths (ed.): A.J. Ayer: Memorial Essays, Cambridge University Press, 1991.